I am sitting at my kitchen table, flanked by my two young daughters coloring farm scenes with crayons. I am reading Lena Dunham’s Lenny letter in response to the court’s ruling in Kesha’s case. I look over at my younger daughter, her chubby fingers with chipped, multicolored nail polish holding a crayon with great concentration.

My heart is sinking.

It has been a few days since Kesha’s request for an injunction to let her out of her contract with Sony and with her producer Dr Luke (whom she alleged raped her, among other things) was denied. It has been the first time I have had the emotional wherewithal to think about its implications. Dunham explains what many of us are feeling about this news: “a special brand of nausea that comes when public events intersect with your most private triggers.”

I have to admit, I am not a lawyer, and I don’t completely understand the ins and outs of this case. What I know is that Kesha has alleged that her long-time producer, Dr Luke, has emotionally and sexually abused her, and that she doesn’t feel safe to continue working with him. She is asking Sony to let her out of her contract so that she can continue her music career in safety. Sony denied her request, so she took them to court. Now a court has denied the injunction that would let her out of the contract.

Officially, she isn’t forced to work with Dr Luke. But she is forced (under the contract’s terms) to continue to record for his label, Kemosabe Records. Many commentors figure that since she doesn’t have to work with him, Dr Luke poses no threat to her, and that this lawsuit is Kesha being needlessly whiny. Dunham explains the challenge Kesha faces now:

“Imagine someone really hurt you, physically and emotionally. Scared you and abused you, threatened your family. The judge says that you don’t have to see them again, BUT they still own your house. So they can decide when to turn the heat on and off, whether they’ll pay the telephone bill or fix the roof when it leaks. After everything you’ve been through, do you feel safe living in that house? Do you trust them to protect you?”

The problem with this case (and with pretty much all rape cases) is that there is no proof of anything. Since the overwhelming majority of rape victims are women, and the overwhelming majority of rapists are men, the discussion devolves pretty much along predictable gender lines. Men are afraid that a woman could cry “Rape!” and their career and credibility would be ruined. For each rape accusation, observers could come up with ten plausible alternate scenarios for why the woman is lying.

In Kesha’s case, the alternate narrative is that she wants more money, and is using a rape allegation as a tactic to renegotiate her contract. Greedy b*tch. Sony and Dr Luke have presented this as the *real* reason for the lawsuit, although they have no evidence for that assertion (even while they criticize Kesha for her lack of evidence).

Let’s assume that that is true: Kesha has some sort of endgame involving renegotiations either with Sony or with another label, and is using this as a tactic to further her plan. What happens if Sony lets her out? Not much. She may or may not renegotiate and may or may not make more money, and Sony may be out a couple million. Dr Luke would continue producing, and Sony would continue to make billions. (Not to mention that Kesha’s career has been on a decline– not a strong negotiating point.)

Now what if Kesha was telling the truth? Being forced to make money for (and continue to be dependent on) Dr Luke for her financial well-being will have a devastating effect on her personal well-being and on her career. She may quit recording. And Dr Luke will continue producing, and Sony would continue to make billions.

Dr Luke could argue that his career would suffer from the allegations. In response, I would present Exhibit A: Chris Brown, still recording after pleading guilty to felony assault.

The fact that the court didn’t give Kesha the benefit of the doubt in this instance, recognizing that everyone else will return to “business as usual” regardless of the outcome, except for Kesha, is a tragedy. Her health, and possibly her career, are collateral damage here, as they can’t be quantified “within the four corners of the contract,” the way commentors and pundits argue.

Women’s experiences and realities will almost always be qualitative and unquantifiable. And since pretty much every narrative tradition has been patriarchal, we all understand stories from the male perspective. It’s a huge paradigm shift for courts (and for society) to “take women’s word for it” that they were victimized, when women have been cast as either the virgin (who wouldn’t have been compromised in the first place) or the whore who was “asking for it.”

Dunham adds:

“The fact is, Kesha will never have a doctor’s note. She will never have a videotape that shows us that Gottwald threatened and shamed her, and she will never be able to prove, beyond the power of her testimony, that she is unsafe doing business with this man.”

The CDC reports that 1 in 6 women (18 percent) will be raped in her lifetime, and 1 in 20 will experience sexual violence other than rape. Adding to that horrifying statistic is the estimated 68 percent of rapes that go completely unreported, and the 97 percent that go unprosecuted. I can’t help but think that the 29 out of 100 cases that are reported but not prosecuted are shelved for lack of evidence.

We have to start valuing the voices of women and men who report sexual assault. That is likely to be all the evidence they will ever have, so if we tell them that that is not enough, that is legally tantamount to saying their assaults didn’t happen.

The way it stands now, there is a one in three chance that one of my chubby-fingered daughters will experience sexual assault. And if that happens, there is a one in 50 chance (out of the victims of sexual assault) that her assailant will see a courtroom. These are screwed-up odds, and we need to thank women like Kesha for going up against them in an attempt for justice.

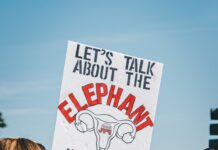

Women’s voices and experiences matter. We need the law to change to value women’s voices. “Innocent until proven guilty” will always favor the assailant in a sexual assault case, so we need to change the paradigm under which these cases are investigated and prosecuted. Because there is no epidemic of falsely accused men going to jail for rape. But there is an epidemic of women being raped and not being listened to.