It is 11:00 PM and Dawn* finally has an opportunity to sit down. She has one hour to herself at the end of each day, which she usually reserves for time to check her Facebook on the cell phone her sister bought for her. Tonight, she scrolls through while talking to me about her life as a mother and caregiver.

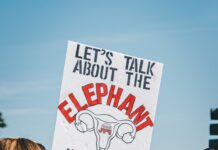

Scrolling through the day’s posts, she reads several from friends and family members that say things like: “Oh, you spent your welfare check on the new iPhone and now you’re broke? Better ask Siri where you can get a job like the rest of us!” and, “For all the taxes they take out of my paycheck, the least they can do is send me a picture of the ghetto family I’m supporting to hang on my fridge!”

“I don’t understand why people think this way,” she says to me, the hurt obvious in her eyes. “How is it that if I hire someone to come and do all of the work that I do, she deserves respect, but because I do it, it doesn’t count as work?”

“I don’t understand why people think this way,” she says to me, the hurt obvious in her eyes. “How is it that if I hire someone to come and do all of the work that I do, she deserves respect, but because I do it, it doesn’t count as work?”

Dawn actually holds two full-time jobs, she just isn’t paid for either of them. One of her?jobs is as a caretaker for her spouse, who is physically disabled due to a debilitating disease that has left him with both severe physical and mental challenges. It is a job that is held, according to the Family Caregiver Alliance, by “65.7 million caregivers,” who “make up 29% of the U.S. adult population providing care to someone who is ill, disabled or aged.”

Another job she performs is one held primarily (although certainly not exclusively) by?women throughout history: childcare. Her toddler son is three and keeps her incredibly busy. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, childcare workers earn an average of $9.38 an hour to “care for children’s basic needs, such as bathing and feeding.”

Dawn does much more than that. In fact, as she describes a typical day in her life, I’m exhausted just listening. Her husband, Andy*, has more than twenty medications that must be organized, dispensed and tracked. There are pharmacies to call and prescriptions to pick up, appointments with Andy’s eight doctors almost?every day, an in-home nurse?who comes every few weeks?to give Andy the hemoglobulin infusions that make his immune system function that Dawn must schedule and prepare for, insurance companies like?Medicare and Medicaid to deal with, and machines and equipment necessary to Andy’s survival to operate and understand.

It isn’t as if the work of being a mother or housewife stops for his illness, either. Dawn does bathe and feed her child, but also monitors and teaches him, reads to him and tries to give him plenty of supervised outdoor time. There are always meals to cook and dishes to wash; there is always laundry to fold and a house to keep clean, as well.

Prior to the illness, Dawn had a full schedule. Andy ran a successful construction business and Dawn kept his books, did his payroll, managed their worker’s comp and liability insurance, tracked spending for taxes, took tools to be replaced and repaired, and sometimes even helped with construction and construction clean-up when it was needed. None of that, according to her, amounted to the responsibility or the all-consuming work of being a mother and caretaker.

“I wouldn’t trade it for anything. I’ve been with Andy since I was 17. He took care of me financially for years, now it’s my turn to take care of him.?And my son, my son is the greatest blessing I’ve ever had. But it’s hard. It’s really, really hard sometimes.”

Now that Andy is no longer able to work and Dawn cares for him and their son full-time, the family survives on less than $1200 per month in a complicated patchwork of Social Security disability, TANF, and food stamps. A small percentage of their $750 a month in rent is subsidized, the rest comes out of their tiny income. Once Dawn pays the electric, the water, the gas, the city utilities, the phone bill (necessary to run Andy’s Life Alert system), their car insurance (necessary to get Andy to endless doctor appointments), puts enough gas in the car to get to all of those appointments, supplements the $112 the family receives in food stamps by buying the rest of their food for a month, and pays for their one luxury (cable television), she has, on average, around $12 left.

“People act like I’m horrible because we have cable. I mean, honestly, Andy can’t go a lot of places outside of doctor appointments. Should he lie in bed and stare at the ceiling all day? Seriously, it’s all we have. It isn’t like we’re living the high life over here. If the baby and I go to do anything else, anything fun, it’s only because my family was nice enough to invite us and pay for it. My sister pays for my cell phone so Andy or medical services?people can call if there’s an emergency, otherwise I could never leave the house.”

So the next time you see one of those memes on Facebook trashing people who receive public assistance benefits, and you laugh, or share it, or even just click like and help to perpetuate the idea that people who need help are just lazy and sponging off others, ask yourself, do you really know who you’re talking about? Are you sure that those people aren’t working, or are they just not performing work as you’ve been taught to define it?

(*Names and details?have been changed to protect anonymity, but the story and all its details are factual and accurate.)